What would new antimicrobial discovery mean for veterinarians?

2021-02-22Study finds promising bacterial ‘hormone’ that may help identify new antimicrobials

Did you know that most antimicrobials are derived from other microorganisms like bacteria and fungi?

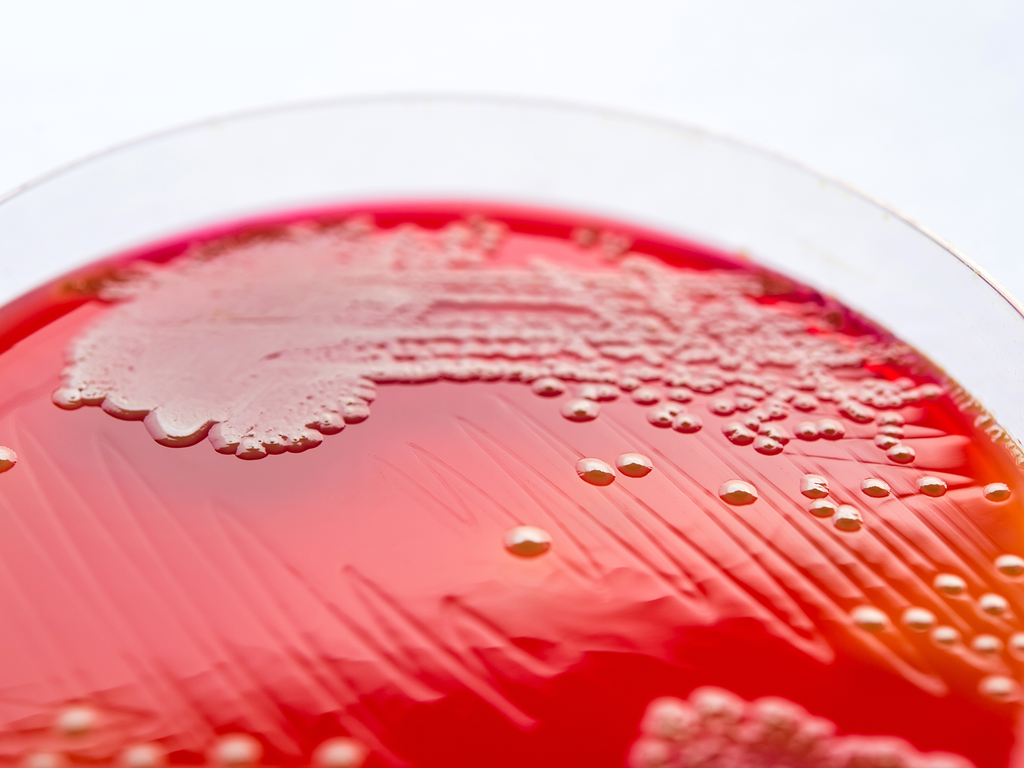

Soil bacteria from the phylum Actinobacteria have been particularly prolific antibacterial producers, and with the increase in antimicrobial resistance, this phylum is again being investigated for potential new antibacterial agents.

In nature, bacteria exist in mixed microbial colonies where there is competition for access to limited resources. Some species are capable of producing molecules that can impede the growth of competing colonies in order maintain their own access to the resources they need to survive and grow. The molecules that we've thus far been able to isolate have become some of our most valuable antimicrobial classes, including the tetracyclines, aminoglycosides, macrolides, and lincosamides, among others.

The naturally occurring molecules produced by the bacteria can be altered in the lab to produce semi-synthetic varieties with slightly different properties. For example, a semi-synthetic derivative may increase target-cell binding, reduce host toxicity, or better target specific organisms. (There are only two fully synthetic classes of antimicrobials in veterinary medicine, the sulphonamides and the fluoroquinolones.)

Unfortunately, in the lab, where pure bacterial cultures are used and culture media provide the necessary nutrients for efficient growth, there is no competition for resources and thus no reason for bacteria to release molecules with antimicrobial properties, even if they may harbour the genetic potential to do so. This makes it difficult for researchers to screen laboratory isolates for new potential antibacterial agents.

New study identifies highly conserved bacterial ‘hormone’ that may help to ‘turn on’ antimicrobial production in bacteria.

A new study by researchers from the University of Warwick in the UK and Monash University in Australia has been looking into how bacterial 'hormones' control the expression of genes related to antibacterial molecule production.

The researchers used a novel technique to help identify how the bacterial 'hormone' 2-akyl-4-hydroxymethylfuran-3-carboxylic acids (AHFCA) impacts gene expression in bacteria and found that is highly conserved among Actinobacteria. This study lays the groundwork for further research investigating whether or not manipulation of this compound can 'turn on' antibacterial production in pure laboratory cultures.

The following quote from the researchers appears in a February 18 article in Bioworld article by John Fox, which you can access here.

"By developing a detailed understanding of the mechanisms controlling antibiotic production, we can design rational strategies for turning on the production of antibiotics that aren't normally made in pure laboratory cultures."

"Such antibiotics are likely to have novel structures and hit new targets, or known targets in new ways, which should enable us to develop antibiotics that circumvent mechanisms conferring resistance to currently used antibiotics."

New antimicrobials considered key to addressing AMR

The identification of new antimicrobials is considered key to addressing AMR, however we also know that resistance to new agents emerges quite quickly, and the economics of developing new drugs which will, by design, be used in low volumes, does little to encourage investment in drug discovery.

New antimicrobials unlikely to be registered for veterinary use

It is generally accepted that any new antimicrobial agents will be limited to use in human health and not made available for veterinary use. A minority in the human medical community argue that antimicrobials should not be used in animals at all, and that even currently available agents should be reserved for human use only. While the removal of antimicrobials from use in animals is unlikely due to considerations for animal welfare and food security, the veterinary profession is also unlikely to gain access to new agents designed to treat resistant infections in people.

So where does that leave veterinarians?

Despite the interesting science associated with these new discoveries, any therapeutic advantages that they may offer will be limited to human health. As such it is imperative for veterinarians to do all in our power to conserve the efficacy of the agents we do have.

This involves working to minimise the use of antimicrobials through improved preventative health, hygiene, animal husbandry and management, infection prevention and biosecurity measures. We also need to ensure that we have the appropriate level of diagnostic evidence to support the presence of microbial disease prior to commencing therapy.

When we are confident that antimicrobial therapy is required, we can follow these six simple prescribing principles to make sure we are prescribing in line with best practice antimicrobial stewardship.

Six simple principles to support best practice prescribing

- Do not use antimicrobials for self-limiting disease

- Where you can, treat topically or locally

- Choose the narrowest spectrum effective agent available

- Use the latest resources to inform dose rate and frequency

- Treat for the shortest duration necessary

- If there is more than one effective agent available, choose the one with the lowest importance rating to human health (ASTAG rating in Australia.)

We have created a poster with these six simple principles for you to print and hang in your practice pharmacy. You can download it here.